Welcome, dear readers, to April, a month variously named sweet and cruel in poetry across the ages, and therefore uniquely appropriate to a series on How to Read Poetry. Over the next four weeks I want to transform you from a sheepish non-reader of poetry into a curious appreciator of it by doing the following:

- Demonstrating that poetry is more than the dry dusty stuff people tried to cram down your throats in high school, and that you’re missing out on something awesome and important by shunning it wholesale.

- Suggesting different ways of approaching poems you’re not understanding to help you figure out whether there’s something in here for you to enjoy or not.

- Introducing you to the fantastic poetry of the authors whose fiction you may already love.

What I won’t do is hold forth about things like the difference between synecdoche and metonymy or why some bits of Shakespeare are written in iambic pentameter while others are written in trochaic tetrameter. I love that stuff, but for my purposes here it’s besides the point. You don’t need to know these things to enjoy poetry; you don’t need to be able to tell the difference between a sonnet and a sestina to be spellbound by them. Rhyme schemes, verse forms and prosody are fascinating things, but my sense is that they’re also intricate and elaborate window dressing that has for too long obscured the window itself.

I want you to look through the window, let your eyes adjust to the light, and start telling me what you see. I want you to experience the feeling that good poetry evokes—what Liz Bourke has called “the immanence of things that know no words,” something that’s “as close as [she] get[s] to religious experience, anymore.” I want you to feel what it means to really click with a poem, to want to memorize it so you can keep it with you always, as close to you as your skin.

Let’s begin.

Why You Should Read Poetry

Part of me is perpetually astonished that I need to explain to people why they should read poetry. The mainstream perception of poetry in the anglophone West is fundamentally alien to me. Over and over I encounter the notion that poetry is impenetrable, reserved for the ivory tower, that one can’t understand or say anything about it without a literature degree, that it is boring, opaque, and ultimately irrelevant. It seems like every few months someone in a major newspaper blithely wonders whether poetry is dead, or why no one writes Great Poetry anymore. People see poetry as ossified, a relic locked away in textbooks, rattled every now and then to shake out the tired conclusions of droning lecturers who have absorbed their views from the previous set of droning lecturers and so on and on through history.

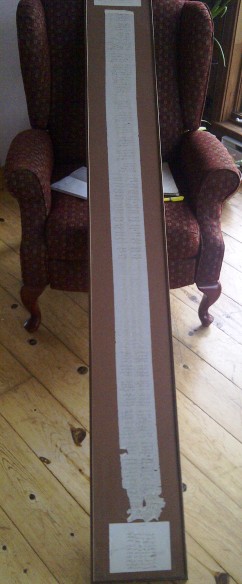

Let me tell you the first thing I ever learned about poetry: it was what my grandfather spoke to keep up morale while imprisoned for his politics in Lebanon, in the ’60s. His extempore mocked the guards, the terrible food, made light of the vicious treatment he and his fellow prisoners received. Someone in a cell next to him was moved enough to write down his words with whatever he had on hand—in his case, a stub of pencil and a roll of toilet paper. We still have it, framed, in my family’s home in Canada.

I was in Lebanon when my parents told me these stories. I was seven years old, and just beginning to read and write poems myself. When my parents told me that my choosing to write poetry was a tremendous act, I believed them. After all, hardly a day went by without people at school, or in shops, or on the streets, learning my surname and asking me if I was any relation to Ajaj The Poet.

I grew up being taught that poetry is the language of resistance—that when oppression and injustice exceed our capacity to frame them into words, we still have poetry. I was taught that poetry is the voice left to the silenced. To borrow some words from T. S. Eliot’s essay “The Metaphysical Poets” and use them out of context, poetry has the capacity “to force, to dislocate if necessary, language into [its] meaning.” In a world where language frequently sanitizes horror—mass murder into “ethnic cleansing,” devastating destruction of life and infrastructure into “surgical strikes”—poetry allows for the reclamation of reality.

I grew up being taught that poetry is the language of resistance—that when oppression and injustice exceed our capacity to frame them into words, we still have poetry. I was taught that poetry is the voice left to the silenced. To borrow some words from T. S. Eliot’s essay “The Metaphysical Poets” and use them out of context, poetry has the capacity “to force, to dislocate if necessary, language into [its] meaning.” In a world where language frequently sanitizes horror—mass murder into “ethnic cleansing,” devastating destruction of life and infrastructure into “surgical strikes”—poetry allows for the reclamation of reality.

Why Poetry on Tor.com

Of course, the poetry I read and wrote when I was seven bore no resemblance to my grandfather’s speaking truth to power. For one thing I was reading in English, not Arabic; for another, I was a child. I was charmed by a poem about a fairy that used a snail’s slime trail for a shimmering piece of clothing. I memorized the songs and riddles in The Hobbit. I fell in love with an abridged version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream that preserved the Renaissance pronouns, such that the first line of the first poem I ever wrote was “O Moon, O Moon, why art thou so pale?”

(Yes, okay, you can stop giggling now. No, really, quit it.)

So the first poetry I read was the stuff of fantasy, and now, 21 years on from that experience, the poetry I love best is still that which is fantastical, which contains some element of the marvellous, the speculative, the strange. It helps that the poetry taught from the canon of English literature is full of fantasy: from the Christian mythography of Paradise Lost to the threatening creatures of Rossetti’s “Goblin Market” to the fragments Eliot shored against his ruin in The Waste Land, poetry was where the most wonderful aspects of my degree in literature lived.

So there is a beautiful intersection, to me, between poetry and genre fiction: in performing that dislocation of language into meaning, poetry essentially does to language what SF does to reality. Poetry takes us out of the mundane sphere of denotative speech and into the realm of the evocative in the way that SF takes us out of the mimetic, hum-drum everyday and into the impossible.

Mostly for the purposes of this series I’ll be drawing on poems I love from Stone Telling, Mythic Delirium, Strange Horizons, Apex Magazine, Ideomancer, Goblin Fruit, Through the Gate, and inkscrawl. Take note of these; you’ll need them for future homework.

TL;DR Summary:

- Poetry is important.

- Poetry is vast and contains multitudes, and will make you feel things you’ll struggle to put into words.

- You don’t need a degree to read, understand, and love poetry.

- You are allowed to read a poem and hate it. Hating a poem does not necessarily mean that you haven’t understood it. Try to figure out what it is you hate, and read a different poem.

Homework:

Here is a poem I would like you to read, right now, immediately, with no preparation except a deep breath and a sense of adventure. It is very short, all of eight lines.

Ready? Go!

“Moral,” by Alicia Cole.

Read it once in your head; stop. Take stock of whether or not it has had an effect on you.

Now, read it again, but out loud, as if you were reading it to someone else in the room.

Comment with the following:

- Whether you loved it, liked it, hated it, or “didn’t get it.”

- As spontaneously as possible, your articulation about why you felt that way. There are no wrong answers! As you leave comments, I will engage with them and ask you questions or make my own comments about your thoughts, potentially with suggestions for further reading.

Tune in next week for stuff about spoken word and the transformative magic of reading poetry aloud.

Amal El-Mohtar is the author of The Honey Month, a collection of stories and poems written to the taste of 28 different kinds of honey. She has twice received the Rhysling award for best short poem, and her short story “The Green Book” was nominated for a Nebula award. She has recently contributed more ramblings on Doctor Who to the Hugo-nominated Chicks Unravel Time (Mad Norwegian Press), and also edits Goblin Fruit, an online quarterly dedicated to fantastical poetry. Follow her on Twitter, where most evenings she posts a link to a single poem and invites people to discuss it under the hashtag #eveningpoems.

I liked it. The tone of the poem is interesting to me and paints a couple of possible pictures. It seems to start of being about a flock of sheep on a hill. The sheep have been scattered. Then the sheep become (or are used as?) wool for a sleeve that is found or created and then used for a coat for a sister who walks into a town where something ominous seems to be happening.

So, the story of the poem seems to be transforming, rather like the wool. Interestingly ambiguous.

I liked it and don’t think I entirely got it.

I think it is about a town that falls prey to some sort of wild beast?

The poem seems to leave information out, and while that does add a kind of mystique to it (which does make me enjoy it more), I just am not entirely sure what she is talking about.

It moves me about as much as poetry ever has, which is to say: it moves me to frustration. I feel like I should nod sagely and stay silent, like I’ve gotten some deep, meaningful impresson from it.

When I read it to myself, I had to read it twice, because I’m a terrible skimmer, and you can’t. skim. poetry. So then I slowed down.

I got wrapped up in the idea that the sheep were not actually sheep, and when I got to “A sleeve in the scrub, blue from elbow to cuff,” I entertained the notion that “sheep” meant “children,” and that this mother was looking for lost children, found a bit of her son, and used his coat for his sister, her remaining child. I daydreamed a bit about what that story would have been like; what might have killed the children; what the terror in the village was. I even wondered briefly if they were being driven to cannibalism of those who had been killed, much like the woman scavanged a scrap of cloth…

And then I realised that I was no longer reading this poem, I was reading a story that didn’t exist, and I should probably get back to the poem.

So then I read it out loud, and got bored with reading out loud, and frustrated with not knowing how to breathe, because these aren’t sentences, and I have no idea how the author wanted them to flow. And I seem to recall being taught that you don’t actually need to pause at the end of each line of a poem, but never being taught where I was supposed to breathe, then.

And then, when I went back to read the poem one more time before writing this, I realized there was an illustration at the bottom, and that maybe this poem was about birds, or something? And I thought the image told a much more interesting story than the poem, and started thinking up storied for the crows (ravens?) in the image … and then I stopped and wrote this, because clearly I had wandered far from the assignment.

And then I considered the title, which doesn’t really help terribly much. Is this a moral? Is this defining moral? (See, that title would go so well with the scavanging mother and the cannabilistic villagers!)

ETA: Oh, sad. After clicking through a bit, that’s apparently just the illustration for the magazine. I had put crows into my imaginary story, and everything. (I’m not being fascetious – this little story did occur to me while reading.)

Also … as someone who generally hates horror anything, I’m a little shocked by the direction of my thoughts.

My reaction: after two readings silently (cannot read aloud right now, tried to mimic process in my head), I think the mother’s son has been killed violently, possibly eaten, but I’m not sure who did it, but it may have been people in the town. Which I find upsetting in a way I do not enjoy.

Thought processes:

“The flock was easier to patch”–than what? Okay, look for that.

The flock’s been scattered. Of “the rest”–presumably the comparison to the flock–all that remains are “tufts” and “a sleeve” on “stained turf.” Okay, that’s not good, whoever was wearing that sleeve has been seriously hurt at the least.

“To which his mother added burlap, made a sister’s winter coat”–so the mother’s son was wearing that sleeve, but it’s now being used for someone else, and the son remains conspicuously absent, so he’s probably dead?

Before this, I felt pretty certain of how I was interpreting the text. Now is where I start feeling very unsure.

“She walked the town silent, her left arm a shield against beasts.” — I can’t tell if the second clause is supposed to be literal or figurative. I also can’t tell if the association I have, of carrying my kids on my left hip with my left arm wrapped around them, is something useful to bring to the poem.

I can’t tell if the last two lines are an explanation for what happened to the kid (I note there are rocks both where the flock & sleeve was and in these lines) or something that is now happening to the mother. I think “the town” is supposed to have done something violent to someone who cried, possibly eaten it, but I can’t tell who “the town” might be or whether eating is actually involved, and I’m finding my trying to conjure scenarios on this topic really rather unpleasant, so I’m going to stop now.

This sort of “C’mon, read a poem!” exercise never works very well with narrative poetry, since it just leads to people trying to make a story out of a poem.

Violence, death, a gathering of resources, and then survival. Rince, then repeat. Tragedy seems like such a quaint notion within such an existance. I wonder what Ajaj The Poet would make of such a setting.

I like it. I don’t love it, but I tend to like either the more explicitly narrative, or the more cruelly abstract, in my poetry, and this is somewhere in between — which maybe means “I don’t really understand it”. Perfectly possible, as I’m never as clever as I think I am, hence the reason I read a lot but am not a good literary academic.

I see an unknown and dangerous, but always possibly present, menace at the wild edges of a scratched-in human space — beasts. I see the daughter shielded as best she can be, by her mother — but more in hope than truth. I see a hard life with narrow bounds, cold wind, scraping by — the sheep, truly, even in this tragedy, would be the greater loss, because they mean a living. Spring coming out of a cold and dangerous season is only a little promise, and the rocks and the sky don’t care.

Well now I have a random Portishead lyric going round and round my head “a mother’s son has left me here”.

I mixed on this. There are aspects that I liked, fond as I am of stark imagery. The open and close were well done, but the middle somewhat clumsy. What with that unweildly sentance, and confused meaning.

So. Sheep being attacked, presumably eaten by a wolf. Such is winter’s woes. But this is easier to ‘patch’ than that which is unspoken. Wolves in morals are often used in association with rapists/pedophiles.

One reading is that by ‘his mother’ the poem identifies that which is missing, or rather whom. The son is found murdered in the field. Hard faced and practical the mother uses his clothes to make a coat (with her burlap poverty) for his sister.

Another is that it was the mother who was attacked, the son narrating. ‘The siring ram found in the hedge, his horns tangled’. Siring implies dominance and sex, horns tangled implies an attempt foiled. The mother murders her attacker, takes his blue (blue blood? Noble to her burlap poverty?) cloth and fashions a coat to protect her daughter from the harsh reality of winter.

She (which the mother or the daughter?) has experiance has a shield, is protected from the ‘beasts’. The uncaring villiage folk who ignore these regular abuses.

I liked it, but didn’t feel like I understood it all. There were glimpses of things, as though I could just start to get the shape of what she was talking about. It had a meloncholy tone, to me, as though there was something missing or desired, almost lament-like. It made me feel a bit sad.

It’s intriguing. It entails a lot of imagery. The ram caught in the thicket at first conjures the image of Isaac the son saved at the last moment from sacrifice. Read again I see the tale of a lost Shepherd Boy. The flock scattered and decimated by a Dire Wolf or other monster, only the sleeve of the coat which had been his older sister’s remains. There is no sign of the boy and the mother weeps as she remembers tenderly mending a hole in the sleeve with the piece of burlap.

The poems brevity adds to its mystery which the reader can explore at their leisure.

It struck with me on the third reading that the poem must be a sequel to the story of the Boy Who Cried Wolf: “a town tired of night criers” being the town that ignored the boy who cried wolf, of whom now only a sleeve is left, although some lambs and the siring ram survived of his flock. The “howl dashed against rocks” to me represents the futility of the boy’s cries for help when the wolf did attack.

I am not sure if “She walked the town silent, her left arm a shield against beasts” refers to the mother or the sister. That frustrates me, as not being clear on pronoun antecedence is a particular annoyance of mine. If it is the mother, to me the point of my interpretation of the poem is that the Boy Who Cried Wolf still had a mother and she still mourned his loss as the rest of the town chose to abandon him as deserving his fate.

Thence comes the “Moral” — instead of, as the fable usually does, presenting a dry moral such as “Liars won’t be believed,” leaving the boy, and the wolf and the town all puppets in the service of the didactic, the poet makes them human, and shows what the actual aftermath of this event might have been.

I wanted to like it, but I too do not feel like I got it, certainly not at first. Even though I’ve read a lot of fantasy, it felt like a foreign language or a private language I was not privy to. After several silent reads and an awkward read aloud I listened to the recording and that helped. Every new sentence felt more like a new paragraph, and even reading aloud I read it much faster than the recording.

I had trouble knowing which bits were literal and which metaphorical. Is it purely metaphorical or is there a snippet of literal story, a “real(-ish)” setting, place, situation embedded in it? The more I read, the more I leaned toward the latter. Literal images, but piecemeal.

After several more reads and glancing through others’ comments I’m growing more certain it is a snippet of horror, not my favorite genre. But the more I read it, the more it unfolds into story and possibility, as it did for another commenter above. It serves somewhat as a writing prompt, which is nice…

So I read some of the other comments, and was surprised at how few people got “The Boy Who Cried Wolf”. It took me three readings to get it, but I got there.

So, from the title, I got that all of that destruction, those lambs eaten, the torn sleeve, the killed boy, were all for the sake of the moral.

The ram caught by his horns is a reference to the Biblical story of Abraham, where when Abraham was ready to obey God’s command and take the life of his only son, God intervened and provided a ram caught by its horns, and the ram was sacrificed in the boy’s place. Only in this poem, the boy was sacrificed in the ram’s place.

Whoa, obviously I COMPLETELY did not get “The Boy Who Cried Wolf!”

Edit: and having missed it, I felt the lack keenly. That recognition snaps into place the things I was fumbling towards understanding and not, to my frustration.

@13 I like this. But then we have to consider the question: Did the author draw from that fable alone, or the folklore that it was a varient of?

As for the christian readings….I’m just not gona see that. I do suspect that there may be a naturalistic nod to Seamus Heaney.

During Max Harris’ obscenity trial in 1944 (for having published the Ern Malley poems), one of the things he said on the stand was that understanding a poem required at least three readings and probably at least a half hour of thought after each.

I note that both tnv and Lady Sybil report having “got” the Boy Who Cried Wolf underpinnings on their third reading. So maybe Harris had something there.

I didn’t catch the “Boy Who Cried Wolf” either. Once mentioned the hooks are quite evident. I guess I should have done the third read through.

Lots of good interpretations here, so will not rehash. I wanted to say that I read the referent of “she” to be unambiguously the sister.

A sleeve in the scrub, blue from elbow to cuff,

To which his mother added burlap, made a sister’s winter coat.

She walked the town silent, her left arm a shield against beasts.

The sister lifts up the arm that is carrying the last remainder of her brother’s garment, the blue sleeve. Just as it has survived that attack, she hopes it will protect her now. The color blue further reinforces this reading for me, as blue is the color of protection in some cultures.

Wow, I go to the Hebrides for a couple of days and return to AWESOMENESS! Thank you so much, every one of you, for your contributions here. I’m going to respond to everyone in sequence, but first I want to offer the following confirmation: having “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” as a context for the poem will definitely kick its intelligibility up several notches.

stevenhalter: I’m very glad you liked it, and especially glad reading the comments gave you additional perspective! May I ask what you mean by the tone, and what makes it interesting to you? Also kudos on seeing a continuity of wool/thread in it – that’s really important.

Skavoovee: May I ask what you liked about it? You are totally correct on the town/wild beast front; as others have noted further down, the missing context is the story of “The Boy Who Cried Wolf.” Also totally correct on the poem leaving information out. It’s a fine line to walk, leaving out enough information to allow for the experience of mystery, but also leaving IN enough information to allow for the pleasure of solving that mystery. Reading it again knowing that the poem begins after “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” comes to an end (er, literally), how does that change your experience of reading it?

arianrose: I’m grateful that you’re not nodding and staying silent! Thank you so much for being honest about your experience. This is exactly the kind of thing I’d like to engage with.

You’re right that you can’t skim poetry. (As an aside, I was skimming these comments the first time through, and I read yours as “I’m a terrible swimmer,” and now I have all these metaphors in my head about poetry as an immersive experience, and how in order to swim you have to learn how to manage sinking and floating in the water before you can move forward, get anywhere – but also how sometimes the point is just to be immersed, as in a bath, and that’s fine too!)

All the wondering that you did, the wrapped-up-edness that you’re pointing out? That’s FANTASTIC. That’s really, really great. To touch on my water metaphor again, it’s like you’ve immersed yourself and are keeping your eyes open under water, taking note of what you see—but then remember you’re meant to be swimming. But it’s totally okay to be immersed and look around! The poem is still giving you something. You’re still interacting with the poem. When you stop reading it, something will linger with you. That story that doesn’t exist is something you’ve found your way to through a door the poem opened.

About reading it aloud: I’m going to talk more about this next week, but for now, if you just go to the poem page again, you’ll see that there’s an audio player just beneath the title, and you can hear the author reading the poem herself. Which is not necessarily the one true way of reading it! I myself would read it much differently than she does. But it might give you ideas.

About the title: I really liked tnv‘s musings on “Moral,” and recommend reading them above, but mainly I think it’s a cue to read the context of “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” into the poem, since it’s a fable with such a well-known moral.

katenepveu: I love the thought processes in your first comment, especially the “look for that” aspect. You’ve identified the fact that the poem’s leading you somewhere and won’t yet tell you where, but allowing you to gauge its direction. I see by your second comment that having “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” as a context really illuminated your reading—but how did that change your enjoyment of it? Was it an “aha!” that now allows you to enjoy other things about it, or do you feel that too much was withheld?

N. Mamatas: I d’know, I think it’s working pretty well so far. Also I’m not sure I understand your comment: you’re saying this exercise doesn’t work with a narrative poem because people make a story out of a poem — that has a story in it? Could you possibly elaborate? And if you have any suggestions I’m open to them. Either way I’m glad of the feedback, and thanks for reading.

bunnycatch3r: I have no way of knowing.

Katharine Mills: Oh, I love your observation about the sheep potentially being the greater loss, and how that affects the reading of the whole. How do you feel about the implication, at the end — “a howl dashed against the rocks was winter’s meat” — that the wolf was eaten?

Amal, I’m still finding it difficult to parse the last two lines–I see you find in them an implication that the wolf was eaten by the town, whereas I thought at first that the boy was eaten by the wolf because the townspeople left him to die–and that is sufficient ambiguity on top of my prior confusion that I find it distressing overall, though this is at least 75% because of the (potential) child harm.

Looking at it again, I almost got the vibe the boy was eaten by the town because he cried wolf too often…

I think of myself as liking poetry, but only of a certain sort, usually older, with strong rhythms and clear, striking images. Mostly with rhymes, too. The stuff you want to read over and over just because the words taste so good.

amalmohtar@22:Thge tone setting words, to me, were words like bawled, tangled, stained, fragility and pretty much the whole last line of:

The first set of words seem to evoke, in me, a feeling that something is wrong, something fragile has broken. Then, the last line seemed to be saying that bad things were coming.

Now that I know the “Boy Who Cried Wolf” connection, I am unsure if the last line is fore or post shadowing. It could go either way.

I didn’t get it. I read it, and read it, and read it, and read it, and I got that it was dark, and maybe about someone (or thing) destroying something else and leaving grief and fear and something else that horrified me in its wake, and that this was the aftermath. But I didn’t see a literal meaning and so looked for metaphorical ones because those would make more sense to me.

What I saw was this: a family with a death of a young man, his sister being made to wear all that was left of him. Was she wearing her heart on her sleeve so to speak? Or was this the important part of her identity now, maybe against her will, maybe with her having no will of her own, because with her being a woman she was less important than even this remnant of the son in the family? And this remnant was also all that protected her from other men now because this piece of a man was more threatening than this living breathing woman, because in rape cultures victims are defined by what they wear. Because morals didn’t govern the behavior of beasts.

Depressing. And the Boy who cries Wolf was the furthest thing from my mind.

I have to be honest here. In school, I was taught that there is no right answer for what a poem (or any other kind of art) means, and I do tell myself that. But struggling with poetry like this can be frustrating to no end, and I always feel like I’m missing something and therefore am something of an idiot. It’s not a rewarding experience. I know some love the struggle, and think that it defines the experience. But to me it seems like a game that I cannot win, a test I cannot pass, and so when I see a post with a poem here, even one written by Neil Gaiman, I pass it by, because I figure “What’s the point? I won’t get what he’s trying to say anyway.” I do appreciate your genuine love for it though, and that and your enthusiasm are what made me give it another shot.

My main reaction on reading this one was indifference, I’m afraid. The main reading I can give it is that the poem is a riddle: “what is this poem about?”

I guessed that it was the aftermath of a wolf (or pack of wolves, more likely; wolves don’t usually act alone) attacking a flock of sheep. I did think of “the boy who cried wolf,” but with only a single phrase to tag that interpretation on (“night criers”) I didn’t see a good reason to pick that particular tale of wolf attack: “night criers” could also be wolves howling at night, and it could be any flock of sheep attacked with wolves.

I don’t get it and I can’t really tell you why, I just don’t. I read the poem six times, one of those times out loud. The process was kind of like this:

First reading: ‘Okay I like some poetry, I’ll try this; Wait, what? What does that even mean? I don’t get it, what do any of those things have to do with each other? I feel confused.’ Second reading: ‘Alright, I’ll read it again and maybe I’ll get it this time… okay no I don’t.’ Third time: ‘Okay maybe reading out loud really will help, aaaaand nope it didn’t.’ Fourth, fifth and sixth time ‘If I just read it enough times, maybe tilt my head a bit and squint at it, I’m sure to get something out of it, right?’

I feel like I’m in school again and my teacher’s shaking his head disappointedly because I don’t see what the really amazing and profound poem he’s presented me with is trying to tell me. Just… I see pictures of sheep and a blue sleeve and someone walking through a town and I have no idea what any of those have to do with each other x.x I sort of get the feeling that there’s something bad at some point in this poem but that’s it.

This is how I feel with most poetry, I feel frustrated and stupid because in general I don’t understand them (or, in the case of school, the few times I liked something and thought I got something out of it the teacher ruined it by making me disect the whole thing into tiny pieces and symbols that just ruined the overall image for me). I’ve occasionally stumbled upon poetry in my life after school and sometimes I do like them, I even have one that I really really love. But occasionally liking something isn’t enough for me to want to read a lot of poems, I’m still more likely to skip them I think. Stories just make more sense to me.

This comes by way of reply specifically to @shellywb and @tara Nightreader, but also as a response to some of the comments I’ve seen here.

The biggest problem for me with reading poetry in group settings is always the other people, because of one very crucial element that we so often forget in reading poetry is that is a SKILL.

We’ve had standard prose structure given to us since infanthood, but haven’t had the same exposure to poetry, and so never developed the same familiarity.

There are some people who have a natural aptitude for accessing poetry, people like Amal who hearing his grandfather had something stir in him when he was just a boy. For the rest of us, like anything else, it is a SKILL gained by hard work, practice, and repetition.

And that is because poetry, very often, is designed to be complex or obscure. Think about it. It uses words in a language that we understand, but breaks many of the “rules” that we were taught in other forms of writing. It uses pronouns without introducing the objects those pronouns represent. It changes topics, settings, and POV without paragraph breaks or other markers to clue us in that something has changed. It uses non-logical connections.

If I were to do any of those things writing an essay or short story or news report or email or any of the other kinds of prose writing that exist, I would be “wrong”; I would have broken the rules and made that prose inaccessible. It would be bad writing.

But in poetry, those things are standard.

If poetry was a clear, easily understood format, it would used for other things too. There’s a reason that the instructions for putting together shelving unit are not given in poetry. So ignore anyone who says that something in a poem was “obvious”. It may have been for that person, but it was most likely not the intent of the poet that it the “obvious thing” be readily apparent.

I too have difficulty understand and accessing poetry, but part of what I’m looking forward to in these posts are figuring out more what I can do to connect with them.

In this case, the homework was to read the poem and see how it made me feel. I didn’t get ANY of the Boy Who Cried Wolf, but I do know how the poem affected my emotions. I identified them and I acknowledged them. For me, that’s “Mission Accomplished” and the rest I will get later.

Youngheart80,

people like Amal who hearing his grandfather had something stir in him when he was just a boy.

And yet,

Amal El-Mohtar is the author of The Honey Month, a collection of stories and poems written to the taste of 28 different kinds of honey. She has twice received the Rhysling award for best short poem, and her short story “The Green Book” was nominated for a Nebula award.

:D

I always like to remind people that lyrics are poetry, which seems to help in two ways. First, it points out that music lovers are poetry lovers. Second, it evokes what I call “the right to speculate.” Many of us have no problem putting our own spin on the meaning of ambiguous lyrics, or even overtly concrete lyrics, just as many of us have no problem reading our own meaning into prose fiction. Supporting such meaning can be trickier, but I am always surprised that people who otherwise happily embrace the idea that a piece of fiction is more than what the author put into it balk at doing the same with a poem. Of course, I also had the benefit of an early education into both reading and writing poetry, which not only helps with understanding it now, but also helps with the basic truth that prose is no more a natural expression of language than poetry.

Using this poem as an example of what I mean about bringing my own meaning to poems in general, I did pick up on the “Boy Who Cried Wolf” allusions on first reading, but other interpretations interested me more (“The Boy Who Cried Wolf” has never been a story to me, but an extended moral, and those are boring). I considered the concept of cannibalism (the description of the landscape and climate both make me think of cannibalistic folklore in Scotland and Scandinavia), or maybe a kind of faerykrusher mashup with “Red Riding Hood” with the color symbolism reversed. The blue and the sleeve and the imagery used for the flock, apt for birds as well as sheep, also made me think “The Wild Swans.” I thought about the history of fabric and clothes making, evoked by wool and the mother’s stitching, how these were often forms of communication among women, when other forms were denied them, and how much more intimacy and depth that gave to the connection between mother and daughter. I thought about the rending of clothes and ritualistic keening in grief, and the patching and mending of clothes, the reusing of cloth, among those who cannot afford to waste necessities like cloth and food, even in grief.

Do many of the things I got out of this poem speak more of what I brought to it than what the author wrote? Of course, but that is the connection I need to say a poem moved me. If I had stuck only to what I felt the author had put into the poem, I would not have found it interesting or successful.

@youngheart80, then I think it is a skilled I am doomed at, at least with the modern notion of poetry. My father read poetry (and stories) to my brothers and me most every night when we were children. There is poetry I love, but it’s rather clear cut in meaning. It just speaks of things precisely, condensed in such a way that that the meaning is crystal clear, and I understand it. Perhaps it’s more old-fashioned. As far as I can tell, I stopped “getting” poetry that was written from the latter half of the 20th c. on. The most recent poets I’ve collected are Octavio Paz and Pablo Neruda. Nothing I’ve read that has been written since has connected with me, well, except Joe Haldeman’s poems.

I get that poetry is a different way of writing. And I get that different generations and cultures write it differently. I am hoping to see what’s in these newer poems for me that I might never have seen before, but this first one doesn’t give me hope. It reminded me of a joke that needs to be explained. Although, maybe it’s offered now, and will be offered at the end of the series in order to let us see it with a new set of eyes.

Until then, since the author asked for honesty I will give it, and hope that the other readers here will not be too impatient with me for not sharing their skill set.

@Rose Lemberg: ACK!! And now I feel like a total and complete idiot.

@amalmohtar: my sincerest apologies.

Okay, before I get into my reaction, for people struggling with meaning:

poetry = tumblr

Specifically, the parts of tumblr that are nothing but people posting references to their favorite fandom. I don’t follow Homestuck, and thus most of the posts on tumblr about Homestuck are incomprehensible to me. I do follow Doctor Who, and Who posts often make me cry. Poetry is often referential, and it often references things outside the text of the poem. Like how tumblr kids reference Homestuck and Who. If you contemplate what external things might be referenced, that can sometimes help. (That’s why people sometimes reference the life of the author. Someone from 1600s Europe is much more likely to be referencing the Bible or Greek myth than a poet from 1400s Japan, etc.)

Anyways, my mind leapt to the Boy Who Cried Wolf around “To which his mother” because the Boy Who Cried Wolf is one of those fables that always picked at me. I didn’t read it in a book of fables as a kid- an adult told it to me, seriously, in an effort to get me to act a certain way, and it bothered me. I instinctively didn’t like adults that tried to make me stop talking.

The narrative that I experienced, reading it, was largely from the perspective of the sister. She knows, now, that if she cries out no one will come. She has to look tough, that’s why her brother’s coat protects her- it’s the symbol of a hard girl, not silly and weak and ignorable. It protects her from the beasts of the town more than the beasts of the wild.

The last line doesn’t insist on cannibalism to me, precisely; just the sort of “pragmatism” of people who are either completely frightened, utterly lazy, or hardened beyond belief. (I don’t know if it’s actually a direct reference, but a google search found me this: http://archive.org/stream/wintershandybook00wint#page/n1/mode/2up ) I think you can read the line to imply the sister reporting the boy’s been eaten, to imply that winter, personified, takes it bit of flesh, or to imply that feeling you get when someone does something horrible and you have no reason to believe it will stop there.

I originally read the last line as saying that the shepherds picked up the pieces of dead sheep and saved them to eat over the winter. A more literal reading would be that they ate the dead wolves (one could assume that sheep, when attacked by wolves, will “howl” (I certainly would!) but that particular word is more commonly used to describe wolf vocalization.) Apparently one of the wolves must have fallen off a cliff and been “dashed against rocks.”

…

Neither of those interpretations seem to hold up on repeated reading, though. A better reading is that after the wolves ate the sheep, all that the town has left for meat over the winter is “a howl dashed against rocks,” which is to say, nothing– the wolves ate it all.

1st time through- Okay, something’s been brutally attacked, ripped apart, probably eaten. Most of the sheep are dead– all that’s left is lambs that don’t have their mothers, and the ram that got trapped in the thicket when he tried to escape. There are people living in the town, but for some reason they’re not safe to be around.

2nd time through- I think a person also died, because of the sleeve.

Then I listened to the audio reading, which didn’t give me much more, except maybe percolating time. I couldn’t fit the title or the sleeve or the point of the story together.

I clicked through to the comments on this post to see what other people thought, but before I even read it, it suddenly clicked for me. Holy shit, it’s The Boy Who Cried Wolf.

That blew me away. It’s a story that’s traditionally told with the implication of “…and it served him right”, while the poem is pointing out that if a real child died, his family would be devastated. It turns it from a rather self-righteous moral to something real and immediate and appalling. I went back and reread it and yes, the title worked, everything fit.

I didn’t get the Biblical allusion to the ram on my own, but after reading the comment that first mentioned it, I really like it.

I like it. A lot. But it does give me the sense that there was a lot I don’t understand, or rather there’s more under the surface, that I would like to have spelled out for me. :-) Lazy, that’s me. I got a feeling of dread and also world-weariness.

OK, now after having read the rest of the comments, including Amal’s, I feel like I can elaborate a bit more:

The fable of the The Boy Who Cried Wolf did pop into my head on first reading the “night criers” bit. But since I’m pretty insecure in these things I sort of dismissed it, since it didn’t seem to fit really with the rest. It hadn’t occurred to me that this poem took place AFTER the fable was over. I think it was “tnv” who made a clear case above for the basis of Alicia Cole’s poem being that fable and their comments made the imagery of the poem snap into focus. I suppose that just means that I need to trust my instincts more! I got distracted (had to go pick up my son from school and do various things before I could return to this) and had basically forgotten my original thoughts until reminded of them later. Convenient, huh?

Other posters reminded me of the ram with the horns tangled being from the biblical story of Abraham and that clicked something in me as well.

Rose Lemberg, thank you very much for illuminating the bit about the blue sleeve. That also makes perfect sense to me and is a useful bit of info to know for the future: blue = protection.

Geoffrey Landis – Hi! – I agree completely about the last line. The howl was all there was left to eat that winter.

Now that I’ve written all of that, I find that this exercise helps me enormously! With the help of all you intelligent and knowledgeable people I feel like my appreciation of the poem is somewhat more justified rather than relying solely on my vague feelings that there is more to it, but that I enjoyed the language and the imagery despite not seeing the picture as a whole.

I’m coming into this a bit late, but here’s my take, both before and after reading the comments.

Before: I adore the flow of the language, especially read out loud. Several of the descriptive parallels caught me–“patching” the flock was easier than patching the boy (whom I presumed to be dead) or his coat. I liked the image of the sister using her arm (echoing the solitary sleeve) as a shield; this, I felt, was a lovely metaphor for learning a moral from her brother’s mistakes. At the end, I felt as if the sister (and town) took it further–a shield is heavy defense, usually coupled with a weapon, so I imagined the “moral” prepared them not only to defend, but to attack the wolf and dash it against rocks. On first read, I am quite fond of the language, the metaphors, and the (I felt) triumphant end.

After: Wow, I think I missed some allusions. Some of them are biblical, so they’re foreign to me. I suspected the Boy Who Cried Wolf was the primary reference, but I wasn’t certain of it. I’ve only skimmed the second half of the comments now–I’ve begun to suspect my appreciation for the poem is only superficial, that I can’t fully it understand it without a toolbox of terms and allusions well beyond my education and experience. Meh.

This is fairly typical for my (admittedly limited) experience in reading poetry. It’s all lovely images, evocative and rhythmic in a way that sticks, until it becomes apparent that I’m missing a deeper meaning and don’t have the knowledge to uncover it (usually I’m informed of this by people who *do* have the knowledge, which is even more discomfiting). I admit to considering poetry a pretentious, ivory-tower art form, for this reason. Modern poetry has never seemed to me to be intended for a general audience–it’s written as an intellectual game, either for a specific subset of readers, or, more often, for others with a background in poetry.

I loved the poem, but am shy of poetry. Color me alienated, I guess. :)

Sarah Grey: I sincerely hope my comment was not one of those that alienated you, and I apologize if it did. Frankly, I don’t think there’s anything superficial about appreciating a poem for the imagery and flow of the language. I mean, if we poets didn’t want those aspects to be appreciated as much as any other, we wouldn’t put so much effort into them!

I think there is a tendency, at least in the English language tradition, to value meaning in writing over other aspects. While I can see how that might be justified in prose, I think it is completely counterproductive in poetry. If meaning is so much more important than form, lyricism, line rhythm, line breaks, striking imagery, precision in word choice as much for the sound/feel as for the meaning, rhyme schemes, stanzas, and all the other things that go into the craft of poetry, then why are we bothering with those other things? I think your approach to poetry is just as insightful and attentive as one which focuses on “true meaning.”

I was really excited to see this. I love some poetry but feel like I don’t get a lot of it.

I didn’t enjoy this poem. I felt like it wasn’t honestly trying to convey a feeling or a story – it feels like it was written to be opaque. Often, our feelings are difficult to understand but that’s all the more reason not to try to obscure it. This poem didn’t seem honest to me. What I like about poetry is either

A) it’s funny or

B) it’s an honest attempt to grapple with difficult subjects or emotions

I don’t like poetry (or prose) that seems to try to be inaccessible.

But, I think it’s cool that others did get interesting things out of it. I look forward to future posts.

@CEWillis

Your poetry = tumblr is the best explanation I’ve ever heard, I think.

@shellywb: I’m with you 100%. The poetry I most enjoy and understand is the older stuff, whereas that from the 20th century (like modern art) just makes me go O_o.

I loved the metaphor you came up with for this poem. To shift away from the literal is a habit (or a skill) which I think I lack.

@amal, I’d have to say I liked the poem, or at least it’s haunted, fairytale atmosphere. I didn’t really get it though and its opaqueness (thanks MelS) left me a bit frustrated.

dammit. *opacity

I’m reminded of Billy Collins poem Introduction to Poetry where he comments that his students want to “tie the poem to a chair with a rope and torture a confession out of it./They begin beating it with a hose to find out what it really means.” I guess the only “meaning” this poem–Moral–has, is in the mind of the author. I don’t think it is intended to have meaning, it is intended to evoke images in the mind(s) of the reader(s). I could make a good poem(s) out of some of these images and other poets, other poems.

First reading: what? is someone dead?

Second reading, slower: oh, it’s the Boy who cried wolf. I get it. How sad that his body is barely cold and his poor mother is grabbing up the scraps of his clothing to repurpose for her living children.

I liked it. It was very powerful, and definitely clear once I took it in, but not a hit over the head. Also, it expanded the folk tale to speak about his family and community and did so very efficiently. Oddly enough, the thing that killed it for me was the passive voice verb in the last line. “Laid bare, a howl dashed against the rocks was winter’s meat” That “was” slowed it down and made it clunky in the final moment when it really needed a strong finish.

I couldn’t do better myself, so I don’t know why I am giving a line note here except that you asked how I liked or disliked it and why, and that last line was the difference for me between “like” and “love”.

I didn’t get it, and so I didn’t like it much. My first read through I kept having to back up and reread because none of the lines seemed to connect to the previous ones and I had to make sure I didn’t miss anything. The read aloud went smoother, obviously, but I still don’t understand. Like… ok, so the first two lines are clearly about sheep, and the third one is probably also about sheep. The next line, I *think* is refering to the coat that comes later in the poem, but it’s in the same sentance with the tufts between boulders that seems to refer to sheep and I don’t know how we got from one to the other. The fifth line is about the coat – I think the mom is adding burlap to the sheep’s wool?? But who is the “he” referred to in “his mother”? The coat is for A sister, not HIS sister- so who is this girl? The sixth line is about a girl walking the streets- presumably the sister in line five is the she in this line- but why is her left arm a shield against beasts? and what does that have to do with the coat or the flock? The next two lines are about the town, presumably the same town that “she” is walking through- but who is howling? Why? How does that feed winter? Why is it tired of night criers (what, exactly, are those?) and vulnerability and again, what does that have to do with the coat or the flock?

So, none of the lines seem to connect to make any kind of sense, and the lines and words don’t have any particular kind of rhythm to it, nor are there series of interesting sounds. It’s got a kind of sad dreary tone in the recording, but I didn’t read it that way necessarily, though I’m pretty sure it’s hard to spontaneously read it as peppy.

Yeah, I don’t get it.

I didn’t get it. But I persevered and read it aloud. I still didn’t get it, but what I did find pleasant was the arrangement of sounds I needed to make with my mouth in order to read it aloud. It flowed easily, as though my tongue, lips and diaphragm were in some kind of dance or even band together.